Five Photographers. A tribute to David Goldblatt: An exhibition of Alexia Webster, Jabulani Dhlamini, Mauro Vombe and Pierre Crocquet

Opening 3 May 2018

Duration 4-31 May 2018

Gerard Sekoto Gallery

at the Alliance Française of Johannesburg

17, Lower park Drive Corner Kerry Road

Johannesburg, South Africa

Mon-Fri 09:00 - 18:00

Saturday 09:00 - 13:00

In celebrating the retrospective exhibition of David Goldblatt at the Centre Pompidou, Paris (21 Feb – 13 May 2018) the French Institute in South Africa will be honouring David’s contribution to photography by having an exhibition of work from 4 photographers that David had selected called ‘Five Photographers’.

Curator:

John Fleetwood and David Goldblatt

Walkabouts:

Saturday 5 May 11h00 with the photographers and the curator

Wednesday 23 May at 12h30 with the curator

Five Photographers

When the French Ambassador to South Africa, Christophe Farnaud, became aware that I was to have an exhibition at the Pompidou in Paris, he suggested that we should celebrate here. He was very open-minded about what form that could take. I thought then that this could be an opportunity to look at some of the photography – really a tiny fraction of the photography - coming from this part of the world today. Let me confess immediately, I am out of touch. I don’t circulate; aside from a few photographers whose names I see in by-line’s, I don’t know who’s doing what, but every now and then I see photographs that fill me with admiration and a sense of gladness for the strength and insight of the vision of photographers working here, very often, with little reward or recognition. So I suggested to the Ambassador and he agreed to an exhibition of photographs to celebrate some of that work. Then I asked John Fleetwood if he would curate the show which I am very happy to say he agreed to do.

Here then are a few photographs of four photographers each of whose work is as different from the others as can be imagined.

John introduced me to the work of Mauro Vombe of Maputo in Mozambique. Many photographers, including some of great fame, have photographed people in crowded trains and buses, but none that I know of has achieved the sense of survival made monumental of which Vombe’s photographs speak. They are completely of the moment and yet beyond time. They put me in mind of Cartier Bresson’s timeless 1948 photograph of people in Shanghai climbing and shoving at any cost to get to the bank and the gold.

Pierre Crocquet tried to interest me in his work at a time when I was heavily committed to a major project. To my shame I failed to respond and when I finally tried to do so, he was dead. There can be few who engaged with paedophilia and child abuse so plainly, frankly and yet delicately as Crocquet. Seldom has any piece of work in photography and words been more frighteningly titled than Pinky Promise. Survival in “Pinky Promise” is in utter contrast to survival in Mauro Vombe’s buses.

When Jabulani Dhlamini was a youngster he frequently heard the names of Biko, Hani and Sobukwe; but without knowing who they were he assumed them to be relatives. He grew up with these assumptions and today has a feeling for them of a certain closeness. Something of that closeness permeates his essay on Sharpeville, the place where 69 black people were killed by the police in 1960 and where Dhlamini was brought up and lives. Sharpeville was and is still a harsh and unbeautiful place. In his pictures Dhlamini shirks none of this but conveys nevertheless the intimacy of family, memory and belonging.

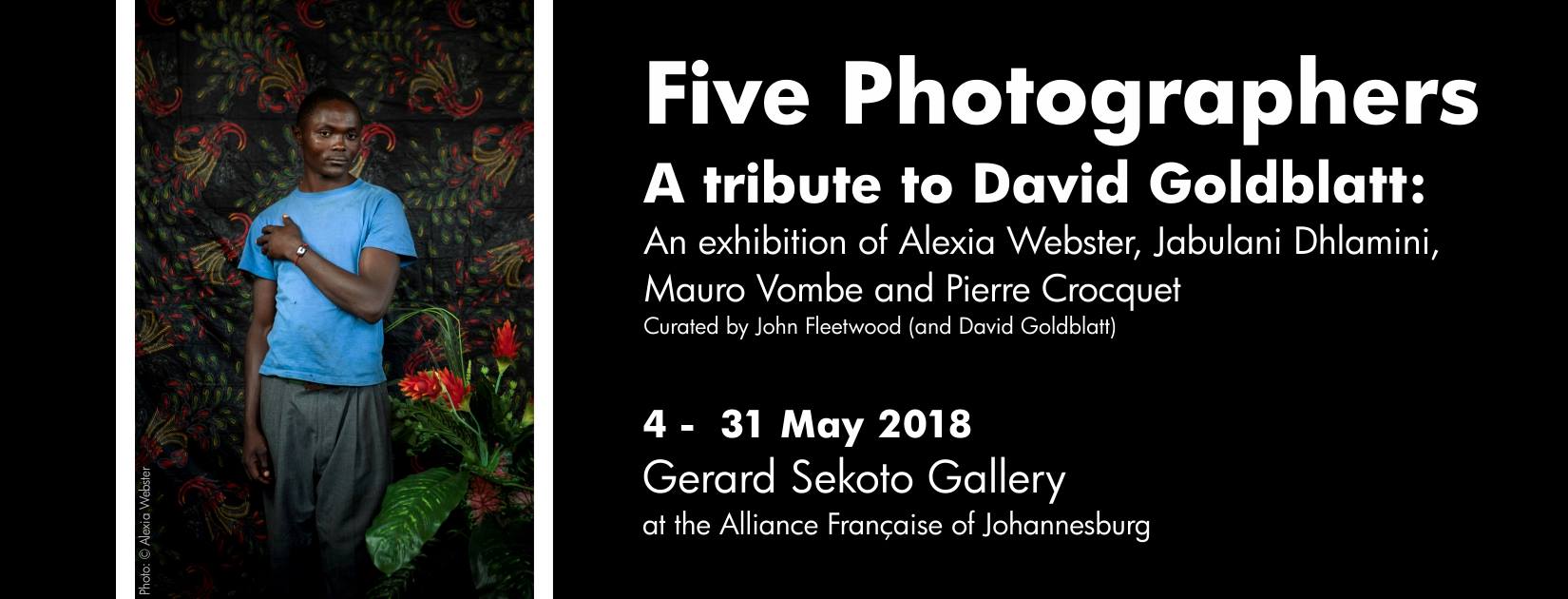

Since 2012 Alexia Webster has made portraits around the corner and in some of the more remote places of the world with a simple knock-down studio background, a flash and reflector, and her camera. People from the area become assistants and often bring subjects to her to be photographed. In a refugee camp some years ago a man complained vociferously to Webster that in his 15 years in the camp he had been photographed many times, yet had never been given one photograph. She now travels with a digital printer and gives prints to all of her subjects.

With flowers and pot plants, cloths, pictures on the wall, her painted or textured backdrops she creates a minute world of almost dreamlike peace. Within it people seem to find themselves, some, as though for the first time. No longer denizens of the street or camp or township of the world beyond, fragments of which Webster often includes at the edge of her photograph, they are in a kind of self-aware tranquillity. Perhaps they take a little of that with them when they return.

I am deeply grateful to the Ambassador, the French embassy, the French Institute and their staffs for making this exhibition possible.

If this was a good idea it would have remained something floating in the air if not for the curation of John Fleetwood. John for whom I have much to be grateful for, has a remarkable knowledge of photography in Africa. With that and an unquenchable energy he has made this show happen.

My thanks to my colleagues and to the sister of Pierre Crocquet for this exhibition.

Lastly, this occasion is a symbolic celebration of my exhibition at the Centre Pompidou in Paris which came about largely through the interest and support for my work, of its Director, Bernard Blistene. That it is a complex and yet seemingly engaging exhibition is to a great degree due to its curator, Karolina Lewandowska, a woman of singular understanding and determination. To these two people, the Goodman Gallery and all who helped them, I am profoundly grateful.

David Goldblatt

Alexia Webster

Street Studios

In Alexia Webster’s ‘Street Studios’, she uses street corners and public spaces to set up outdoor photo studios in different communities. Passing families and individuals are invited to interact to create portraits with the photographer. In these stories, notions of belonging intertwine with the constructed nature of the encounter. She has created street studio’s in Cape Town, Johannesburg, refugee camps in DRC and South Sudan, rock quarries in Madagascar, and in Mexico and India.

Alexia Webster is a South African photographer. Her work explores intimacy, family and identity across the African continent and beyond. She was awarded the Artraker Award for Art in Conflict, the CAP Prize award for Contemporary African Photography, and she received the Frank Arisman Scholarship at the International Centre of Photography in New York City. Her work has been exhibited in South Africa, United States, Europe and India. Most recently she travelled to Juba, South Sudan and Tijuana, Mexico as part of an International Media Foundation fellowship.

Jabulani Dhlamini

Recapture

Jabulani Dhlamini’s series ‘Recapture’ is about the memory and remembrance of the 1960 Sharpeville massacre, a turning point in South Africa’s history. He transforms mundane objects and spaces - the traces of eyewitnesses’ memories - into (anecdotal) monuments, reminding us of the past in the present – and the present in the past. Through these memories of trauma and violence, ‘Recapture’ brings a resonance to the collective memory of Sharpeville.

Jabulani Dhlamini was born in Warden, South Africa in 1983. He lives and works in Johannesburg. His work deals with memory and remembering, traumas of the past and photographs as monuments. He is the Manager ‘Of Soul and Joy’, a project teaching photography skills to youth from disadvantaged backgrounds in Thokoza. After his studies at the Vaal University of Technology, Dhlamini was the recipient of the Edward Ruiz Mentorship 2011/12 at the Market Photo Workshop. He has exhibited his earlier series uMama at The Photo Workshop Gallery and Goodman Gallery Cape Town and Recapture at the Goodman Gallery Cape Town.

Mauro Vombe

Passengers

Mauro Vombe’s work ‘Passengers’ deals with the inhuman conditions of informal public transport in Maputo, Mozambique. The powerlessness of the passengers is bared through their uncomfortable, cramped, disembodied and isolated figures and expressions. The series, as a social document, examines the passive nature of being a passenger – perhaps a metaphor for the human alienation in many encounters with power and capital.

For many people around the world this experience is immediately recognisable. On a daily basis, it is often the poor who are rendered powerless and stripped of their humanity through the basic act of going to work, going to the shops etc.

Mauro Vombe, born (1988) and based in Maputo, Mozambique, started photographing in 2006. His work connects to his earlier experience in theatre, unveiling hidden feelings and creating a form of collective or individual representation, and finds resonance from his work as news and events reporter. Vombe has received numerous awards locally and internationally. He participated in an exhibition dedicated to the 40 years of Mozambican photojournalism at Foundation Fernado Leite Couto in 2015. In 2017 he was an invited participant in the ‘Catchupa Factory’, in Mindelo, Cape Verde. In 2018 he was shortlisted for the democraSEE 2 award.

Photo: would like to thank the Centro Cultural Franco-Moçambicano (CCFM) and the Alliance Française for their support towards Mauro's transport and accommodation.

Pierre Crocquet

Pinky Promise

The late Pierre Crocquet produced ‘Pinky Promise’, a work dealing with stories of victims and perpetrators of child sexual abuse. His photographs, severe, stark, yet delicate, reference the complexity, atrociousness and painfulness of these situations. The photographs are only a part of the extended and personal research that he conducted about abuse, survival and healing. The publication ‘Pinky Promise’ deals with the lives of three paedophiles, and five victims of childhood sexual abuse.

Pierre Crocquet was born in Cape Town in 1971, grew up in Klerksdorp and died in 2013. Early in his career he focused on countering stereotypes of Africa in his publications Us (2002) and On Africa Time (2003).Crocquet spent considerable time photographing jazz and in 2005 exhibited this as Sound Check with a book published in the same name. In Enter/Exit, he documents Karatara, a tiny community on the edge of the Knysna Forest. It was published in 2007. Crocquet started working on Pinky Promise, dealing with childhood sexual abuse in 2009 and in 2011/12 published his book/exhibition.

With thanks to:

Alliance Française

Institut Française d'Afrique du Sud

Goodman Gallery

Galerie Seippel

Jeannine du Venage

Colleen Alborough

Lightfarm

Silvertone

Fourth Wall Books

Wessel Snyman Creatives

Bidvest Soho

Posted 30 Apr 2018